Introduction

Sussex is a county on the south coast of England, bounded by the English Channel on the south, by the coastal counties of Kent, to the east, and Hampshire to the west, and by the inland county of Surrey to the north. In shape it is a narrow rectangle, measuring some 75 miles (120 km) from west to east, along the seashore, and a maximum of 27 miles (43 km) from north to south. It is the 13th of the English counties in order of size, with an area of 934,851 acres (378,325 hectares).

Landscape, geology and building stones

The landscape falls easily into three main areas. Inland is the Weald, originally a lowland area of dense woodland on a heavy clay soil (the Low Weald) combined with uplands on a lighter, sandy soil (the High Weald). The Low Weald runs in a band from the headwaters of the River Arun, around Horsham and the Surrey border, SE towards Lewes and Hailsham, with the High Weald to the north and east along the Kent border. South and west of the Low Weald are the chalk South Downs, which run eastwards from the Hampshire border to meet the sea in the spectacular cliffs at Beachy Head. Finally there is an alluvial coastal plain at the western end of Sussex, around Chichester, Bognor and Selsey Bill, and with this must be associated the marshland of the coast around Rye and Winchelsea in the east. The two are linked by the phenomenon of Longshore Drift, whereby the steady eastward flow of the English Channel has carried silt with it, eroding the coastline in the west and building it up in the east. Thus prehistoric Selsey extended much further south, while the sites of Rye and Winchelsea, both more than a mile inland now, were on the coast. The highest points are Ditchling Beacon in the South Downs (823 feet) and Crowborough Beacon in the High Weald (792 feet). The hills of the Weald are of sandstone; varying in colour from buff around Horsham, to brown around Pulborough and greenish north of Midhurst, where it is the same as the Burgate stone quarried over the border in Surrey. The chalk downs were a source of flint, and the widespread clay provided brick. The main rivers are, from west to east, the Arun which rises near Horsham and runs west and then south through Pulborough and Arundel flowing into the Channel at Littlehampton; the Adur which rises near Hickstead and enters the sea at Shoreham; the Ouse which also runs southwards from the Weald and reaches the sea at Lewes, and the Cuckmere, which flows into the Channel at Cuckmere Haven between Seaford and Beachy Head. Mention should also be made of the Rother, which forms the boundary of Sussex and Kent between Rye and Northiam.

Settlement and main towns

Except along the coastal plain medieval nucleated settlements were sparse; a pattern confirmed by the evidence of deserted medieval villages. Elsewhere there is evidence of a uniform, medium to high density of dispersion for isolated farms and hamlets. Domesday woodland data are distorted by the fact that areas of woodland were recorded under the manors to which they belonged rather than at their actual locations, hence while the Survey suggests that the Weald was devoid of woods it is reasonable to assume that it contained little else.

History of Sussex

Roman Sussex is represented by the city of Chichester (Noviomagus Regnum), which replaced the old centre of the pre-Roman tribe of the Regni at Selsey. Their chief, Cogidubnus, seems to have had a Roman education and to have welcomed the invaders, becoming a client king. To the west and east of Chichester the great villas of Fishbourne and Bignor have been excavated. Other Romano-British centres were at Hassocks (near Burgess Hill) and Plumpton These were linked by a Roman road that joined Stane Street, the major road from Chichester to London in the region of Pulborough. Towards the end of the Roman occupation, after c.270, the coastline came under attack from Germanic raiders and coastal defences were reinforced by the strengthening of the defences of Chichester and the construction of a chain of forts. The military harbour of Anderida (Pevensey) was strengthened too, and a new masonry fort built c.370, but the Romans left in 410, leaving Sussex to the Romano British leaders who apparently retained the strongholds of Chichester, Hassocks and Pevensey.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded the arrival of the Saxon Ella and his three sons in ships, apparently at Pevensey, and this date is normally taken as the beginning of Sussex as the land of the South Saxons. The Chronicle’s version of events is a bloody one, but it is usually assumed that most of the indigenous Britons were not slaughtered but fled either westwards or learned to live with the invaders, eventually being absorbed by intermarriage. Most of Sussex was organised as a distinct political unit, but its boundaries do not seem to have corresponded with those of the traditional county. The centre was around Chichester and Selsey, now in the extreme west, and the South Saxon kingdom extended westwards into modern Hampshire, but only as far east as the Ouse and Cuckmere valleys. The rest of the present county, up to the Kentish border, was occupied by a shadowy tribe called the Haestingas.

By 825 Sussex had come under the control of Egbert, King of Mercia, and at some time thereafter assumed the status of a county. It was divided into six rapes; Chichester, Bramber, Arundel, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings. By the time of the Domesday Survey, each rape was a strip of land running from the coast to the northern county boundary; each was centred on a castle; and each was held by a single trusted tenant-in-chief. This, of course, was to protect England from invasion and to secure lines of communication with Normandy. Each rape was divided into hundreds, and there were sixty of these in 1086. The division into East and West Sussex for judicial purposes dates to 1189. By the 16thc East and West Sussex had their own Quarter Sessions, although the divisions were not called counties before 1888, when the Local Government Act recognised the two as administrative counties while retaining Sussex as a ceremonial county with one Lord Lieutenant. In 1974 the Lord Lieutenant of Sussex was replaced by one each for East and West Sussex. Lewes is the county town of East Sussex and Chichester of West Sussex. Until 2000 Chichester was the only city in Sussex, but in that year Brighton and Hove (which had been created a unitary authority in 1997) was given city status.

Domesday Sussex

Before the Conquest the greatest landowners in Sussex were King Edward and his immediate family, who held 400 hides, and the House of Godwin. Earl Harold’s holdings were greater even than the king’s, amounting to 1100 hides, more than 1/3 of the county. Curiously King William did not retain this enormous holding. In 1086 he held only 2 manors: Harold’s great manor of Bosham, rated at 38 hides, and Rotherfield. The great ecclesiastical landholders were the Archbishop of Canterbury, who had major holdings in Sussex including the manor and hundred of South Malling, rated at 80 hides, and a string of other manors in the county. The Bishop of Chichester’s holdings were mainly in the west of Sussex and the Abbots of Westminster, Fécamp, and Winchester and the bishop of Exeter also had significant holdings. For the rest of the county, five of William’s great secular magnates, were each awarded one or more rapes. Chichester and Arundel in the west went to Roger de Montgomery, Bramber to William de Braose, Lewes to William de Warenne, Pevensey to Robert, Count of Mortain and Hastings to Robert, Count of Eu.

Religious history

According to Bede, organised Christianity was established in the kingdom of the South Saxons by St Wilfrid, the exiled Bishop of York, c.680-81. During his stay (c.680-86) Wilfrid founded a monastery at Selsey, a former royal estate given to him by King Aethelwealh, probably at Church Norton, by the entrance to Pagham Harbour. After Caedwalla conquered the South Saxons c.685, the area became part of the diocese of West Sussex, with its seat in Winchester, but a bishopric of Sussex was established c.705, and Wilfrid's monastery was taken over as the episcopal seat. The bishopric does not seem to have been particularly strong, and by 1066 the Archbishops of Canterbury owned slightly more land in Sussex than did the Bishop of Selsey, which was one of the poorest bishoprics in England. In 1075, the see was transferred to Chichester.

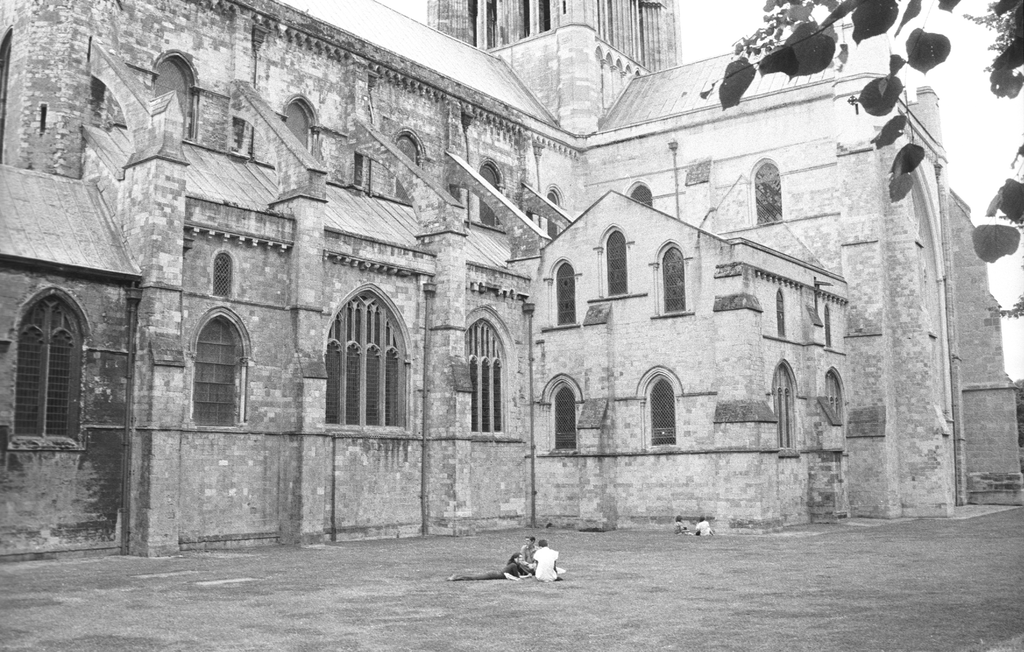

Chichester Cathedral from the NE

The list of major religious houses in the county is headed by Battle Abbey, founded by William c.1070 on the site of the Battle of Hastings. The abbey was heavily endowed and was free of episcopal control, although its second abbot, Gausbert, was blessed by the Bishop of Chichester in 1076. The church was consecrated in 1094. After the Dissolution the house was given to Sir Anthony Browne, Henry VIII’s Master of the Horse, and he was responsible for the destruction of the church and cloister.

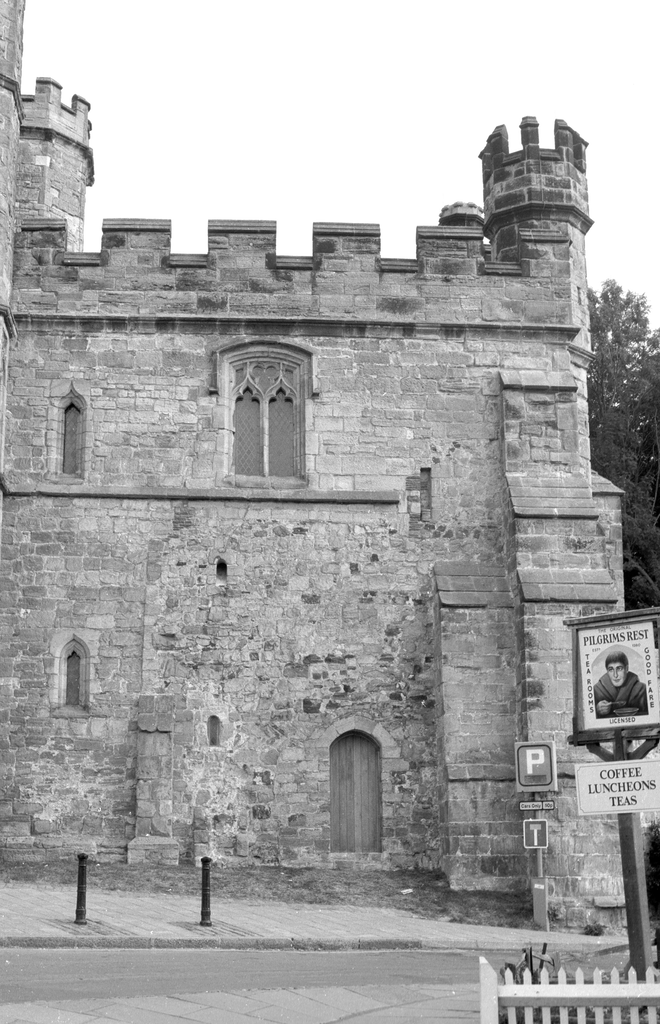

Battle Abbey Gatehouse

The Cluniac priory of Lewes, the first house of that order in England, was founded in 1070 by William de Warenne and his wife Gundrada. The first church was that of St Pancras, recently rebuilt in stone by William de Warenne, which was to become the infirmary chapel of the priory. The original endowment included this church and the land surrounding it, and land at Falmer and Balmer as well as Wiiliam's Norfolk manor of Walton. This was enough to support 10 monks, but the monastery grew through the gifts of William and his successors. The new great church, built on the model of the mother house (Cluny III) was dedicated in c.1095, also to St Pancras. The priory was formally surrendered to the Crown in November 1537, when the prior Robert Crowham, received a pension and a prebend at Lincoln cathedral, and the 23 monks and 80 servants were pensioned off. The priory and all its lands were granted to Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex.

Lewes Priory - the remains of the first church

In 1086 'the clergy' or 'clerks' (clerici) of Boxgrove (Bosgrave) church held one hide of land, a reference which has been interpreted to mean the church was collegiate. It was given to the Benedictine abbey of Lessay in Normandy in 1105, by Robert de Haye, and was established as a priory c.1117. Initially the monks numbered three, but the number was raised to 15 by the middle of the century. In 1537, the Priory was suppressed and sold, and the parish moved into the E end of the church, converting the former pulpitum into a W wall and leaving the rest of the nave to fall into ruin.

Boxgrove Priory, chapter house entrance

Sele Priory had its origins in a college of secular canons established by William de Braose at his castle of Bramber in 1073. In 1080 a more ambitious project for a Benedictine Priory dependent on St Florent de Saumur was established at Beeding, or Sele as it was to become, staffed by monks from Saumur and funded partly from the holdings that had been granted to the Bramber college. It grew in value and possessions, and as an alien house was seized by the king in the 14thc. It passed eventually into the hands of Magdalen College Oxford.

The only Cistercian house in Sussex was Robertsbridge, founded about 1176 by Alvred de St. Martin, sheriff of the rape of Hastings, and the VCH records six houses of Augustinian canons and one of Augustinian nuns, three Premonstratensian houses, two Templar and one Hospitaller preceptories, eight mendicant houses and significant numbers of hospitals, collegiate foundations and alien houses, mostly small foundations.

Romanesque architecture and sculpture

With 174 Romanesque sites on our database, Sussex is one of our richest counties, perhaps unsurprisingly as it was here that William the Conqueror landed from Normandy in 1066. There are substantial standing remains of Battle Abbey, but the only in-situ sculpture of the 11thc are capitals in the Great Gate and on a stub of the west front of the church that survives attached to the W range of claustral buildings. These capitals are of simple block or cushion form, as are excavated capitals now in various English Heritage stores. The cathedral of Chichester was built after the see was moved there from Selsey, but how long after is disputed. William of Malmesbury’s assertion that it was built a novo by Bishop Ralph de Luffa (1091-1123) has not been universally accepted by later scholars; most of whom favour the view that it was begun rather earlier by Bishop Stigand.

Corbels at Chichester and Bosham

The early work is dominated by a wide range of volute and cushion capitals, and corbel tables related to work at Bosham, and (less convincingly) Boxgrove. The Chichester Reliefs of c.1125-50, however, are the main reason to visit Chichester.

The Raising of Lazarus relief at Chichester Cathedral and a detail

Parts of the monastic buildings of Lewes Priory still stand, but the sculptural remains are mostly to be found in gardens and built into walls around the town and the local area. Churches outside Lewes with re-used priory stones are at Beddingham, Ringmer and Rodmell, but the majority of carved stones are held in the Anne of Cleves House museum, Southover.

Sculptural fragments from Lewes Priory re-used on site and at Beddingham church

The tomb of the foundress Gundrada, one of the high points of Sussex Romanesque, is now in Southover church. Boxgrove has significant remains, much of it, including most of the nave arcades and the chapter house entrance unroofed and badly weathered. At Arundel Castle, the SE gatehouse may date from Roger of Montgomery’s time, but it is completely unadorned. The sculpture that does survive, on the keep doorway, hall windows and various loose stones, dates from the mid-12thc or later.

Eleventh-century capitals at Sompting and Selham

In parish churches, 11thc. work may be seen at Sompting, Botolphs, Bramber and Selham. Steyning is a rich Romanesque treasure chest with work from c.1100 and from the second quarter of the 12thc, the latter comparable with sculpture at Amberley.

Sculpture from c.1100 and 1140-50 at Steyning

There is a fine display of beakhead ornament at Tortington, while the Shoreham churches, Old and New, both contain rich displays of mid-12thc decorative sculpture.

Beakhead on the chancel arch at Tortington

Important relief sculpture can be seen at Peasmarsh (beast panels), Bishopstone (grave slab) and Seaford (St Michael relief).

Relief panels at Peasmarsh, Bishopstone and Seaford

By far the commonest type of font in the county is the Sussex marble type, usually consisting of a square bowl with arcaded faces, carried on 5 shafts and made of a material similar to Purbeck marble but with larger fossils.

A typical Sussex marble font at Rudgwick, and a detail of the stone

The stone is technically a large Paludina limestone, otherwise known as Petworth Marble, Bethersden Marble or Laughton Stone. There are 42 Romanesque sites in Sussex with such a font, and they were exported throughout S and E England, appearing as far away as Essex, Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Suffolk.

In addition to these, Sussex can boast a few important fonts, including two basketweave fonts at Denton and Lewes, a font carved with interlace designs at East Dean, and the elaborate historiated font at St Nicholas, Brighton.

Fonts at Brighton and East Dean

Recording

Recording was carried out by Kathryn Morrison with assistance from Ron Baxter, largely between 1989 and 2001. Photography was carried out using a Nikon FM2 with Kodak T-max b/w film. Site reports were written by Kathryn Morrison. The CRSBI would like to thank the clergy and churchwardens of Sussex and the vergers of Chichester Cathedral for their forbearance and assistance.

Short bibliography

- L. André, ‘Fonts in Sussex Churches’, Sussex Archaeological Collections 44 (1901)

- Antram and N. Pevsner, The Buildings of England, Sussex East with Brighton and Hove, New Haven and London 2012.

- Dallaway and G. Cartwright, A History of the Western Division of the County of Sussex. 2 vols, London 1815-30.

- F. Drummond-Roberts, Some Sussex Fonts Photographed and Described. Brighton 1935.

- Gibbon, ‘Dedications of churches and chapels in West Sussex’, Sussex Archaeological Collections 12 (1860), 61-111.

- Harrison, Notes on Sussex Churches. Hove 1908 (4th ed. 1920)

- Hobbs (ed), Chichester Cathedral. An Historical Survey. Chichester 1994.

- W. Horsfield, The History, Antiquities and Topography of the County of Sussex. Lewes and London 1835.

- Nairn and N. Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth 1965.

- Roberts, Twelfth century Church Architecture in Sussex, 1988

- The Victoria History of the County of Sussex, vols 1-7, 9 (1905-2009).

- Zarnecki,`The Chichester Reliefs', Archaeological Journal, 110, 1953, 106-119.