The Corpus of ROMANESQUE SCULPTURE in Britain & Ireland

Castle

Knaresborough is 4 miles E of Harrogate. The castle is now a ruined keep in a large public garden overlooking the gorge of the river Nidd. No twelfth-century remains are visible, though foundation levels and some remains of this period have been found in excavations. There is unfortunately no sculpture which has come to light and so this entry is for information only; see the entry for Knaresborough church.

Castle

The keep of Lancaster Castle is a four-storey tower, which is 20 m high (albeit the upper storey may have been heightened or added at a later date) and has shallow pilaster-like buttresses at the corners and at the centre of each side. The outer walls are approximately 3 m thick. There is a spine wall running E-W which divides the keep internally.

The original main entrance of the keep was via a long set of stone stairs to the 1st floor on the S side, still extant until the 18thc. This elevation is now hidden by the Debtors' Wing of 1796. The W side of the keep is also hidden by the building of the new Shire Hall and Crown Court, begun after 1796. The 1796 prison for male felons is built on the N side of the keep. These additions were all designed by Thomas Harrison, albeit the Shire Hall and Crown Court were finished by Joseph Gandy.

Adrian's (also referred to as Emperor Hadrian's) tower, in the S-W corner of the Castle, has 13th-c style masonry internally, but was entirely refaced externally at the end of the 18thc.

The imposing gatehouse was built by Henry IV after 1399. It has been suggested that the lower levels of the gatehouse contain earlier work from the early 13thc. However, nothing relevant in terms of Romanesque sculpture was observed. The same is true of the Well Tower to the E of the gatehouse, which was largely built in the 15thc. Some structural timbers were dated by Oxford Archaeology North using dendrochronology to a primary phase after 1265, and later refurbishment or building to the late 14thc or early 15thc. Any evidence of earlier building from the 13thc in the lower levels did not include any Romanesque sculpture.

Castle

Berkeley is situated on the English side of the Severn estuary in the Vale of Berkeley, some 10 miles SW of Stroud. A stretch of the Little Avon River runs to the S of the village to enter the estuary just over a mile to the west. The castle is on the SE edge of the village and consists of an approximately square courtyard with a roughly circular shell keep at its NW corner. The Great Hall occupies most of the E range with the service quarters to the N of it and the State Lodgings to the S. The Inner Gateway is at the S end of the W range, and the Outer Gateway is some way to the W of this. The land falls away to the S and E, so that the castle dominates the view from Berkeley Heath. Most of the castle is 14thc, but the shell keep and the Great Hall are 12thc in origin and retain some original features.

A castle was erected here in 1067 by William Fitz Osbern, Earl of Hereford (d.1071), comprising a motte and bailey with a timber keep on the motte. In the mid-12thc the motte was surrounded by the present shell keep, and was levelled within the shell wall, so that the ground is some 20 ft higher inside than it is outside the shell keep. This work was carried out by Robert Fitz Harding, immediately after he received the castle from Henry of Anjou (later Henry II) in 1153. The keep is approximately circular and originally had round bastions to the NE, NW, SE and SW. Only the NE bastion (with an elaborate 12thc window) and the SE bastion remain; the NW bastion was replaced by Thorpe’s Tower in the 14thc, and the remainder of the W stretch of the shell wall was destroyed by a Civil War battery from an emplacement on the roof of the nearby parish church. It was consolidated but the SW bastion was not rebuilt, and the shell wall was never rebuilt to its original height on this side. The keep is of reddish coursed sandstone rubble construction with pilaster buttresses, but this structure survives only on the S and SW sides, the remainder having been rebuilt. On the E face of the keep, between the two surviving bastions, is a forebuilding in the form of a rectangular tower built against the shell wall. It was not built with the wall, but added slightly later in the 12thc. This contains the staircase leading to the elaborate main E entrance doorway to the shell keep. The forebuilding has been considerably altered in later centuries.

Further 12thc fabric is found in the Great Hall, built against the E curtain wall. The Great Hall was rebuilt in the 14thc and extensively restored and remodelled by the 8th Earl, who succeeded to the Berkeley estates in 1916, when he found the castle in an advanced state of disrepair. As a result of these restorations, fabric which appears to be 12thc may not be original. The rectangular hall has its high end at the south, and at the north is a screens passage with a gallery above, divided from the main space by a wooden screen brought from Caefn Mably (Glamorgan). Along the east wall are three tall, round-headed window embrasures, and these are 12thc in origin but restored. 12thc chevron voussoirs have been reused in the doorway from the Keep Garden into Thorpe’s Tower, and these are also described here. Finally the Treasury contains four carved stones of 12thc date. Their provenance is unknown, and they may not be local or even British, having been amassed by the 8th Earl, a voracious collector.

Castle

Skipton is at an important meeting of roads: W to Clitheroe, NW to Appleby, E to Ilkley and Leeds; SE to Bradford. The town is surrounded by fells, but with an open passage of lowland along Airedale. The name means ‘sheep town’; Sheep Street is a branch of High Street, and both seem made for markets.

The original plan of the Norman castle is not known. Two early round towers on the W side flank the round-headed entrance to the Conduit Court, the heart of the castle with its celebrated yew tree. There are some plain slit windows in these towers, and chambers within them. Much enlargement took place in the 14thc, and rebuilding in the 17thc, as well as at other periods. However, the site, overlooking the precipice along the Eller Beck on the N side and the planned town of Skipton to the S, is no doubt basically ‘Norman’. The parish church, with no remains of our period, is at the top of High Street and immediately west of the outer gateway to the castle.

There is a plan of the present castle in Gee (1968, 28). A plan of the whole church and castle area is in the proceedings of the YAS Excursion in 1899. An 18thc plan is reproduced in Leach and Pevsner (2007, 705).

No Romanesque sculpture.

Castle

Ludlow Castle is sited on the western edge of the town, and to its west the land falls away towards the River Teme. It consists of an approximately square enclosure surrounded by a curtain wall, and in the NW corner of this is the Inner Bailey, surrounded on its south and east by the castle ditch, and inside this the Inner Bailey wall. The oldest building on the site is the massive gatehouse keep, or Great Tower. This dates in its original form from the late 11thc., but has been considerably modified. In the early 12thc. the gatehouse was increased in height to four storeys, with a two-storey hall on the first and second floors. In the late 12thc. the entrance was blocked, and a new arch cut through the inner bailey wall immediately E of the keep. Finally, in the 15thc. it was reduced in size, the N wall was rebuilt and floors were inserted in the hall to create new apartments. Some Romanesque windows survive in the keep, as does the original entrance passage (now blocked) with blind arcading on its side walls and the remains of a doorway in the E wall. The main castle buildings form the N range of the Inner Bailey, and consist of the late-13thc. Great Hall with a solar wing to the west, both begun by Geoffrey de Geneville (d. 1314) and his son Peter. The western solar was completed by Roger Mortimer, who took possession in 1308, and he also built a second solar block east of the hall, with a garderobe tower in the outer wall. The kitchen is detached from the Great Hall, standing in the Inner Bailey with its doorway facing that of the hall. No doubt a wooden passageway linked the two. Returning to the N range, to the east of Roger Mortimer's solar is a set of lodgings built in the 16thc., usually called the Tudor block. The chapel, with a circular nave, stands to the E of the Inner Bailey and is the subject of a separate report. Finally, E of the present Inner Bailey are the Judge's lodgings, completed in 1581.

Castle

The castle extends along a limestone promontory, at the top of the tall, sheer cliff that forms the Welsh bank of the river Wye. Here the river turns eastwards from its general southern course, before turning south again to flow into theSevernestuary some 3 miles to the south at Beachley Point. The castle and town are thus contained within a loop of the river, so that the castle, on its lofty ridge, commands a considerable stretch of it in both directions. Inland of this ridge the ground falls away sharply to an area called the Dell. The castle is dominated by the late-11thcGreatTower, traditionally attributed to William Fitz Osbern, Earl of Hereford (d.1071). This must have been surrounded by a curtain wall, and the topography of the site suggests that it enclosed two baileys to east and west of the tower. When the castle passed to William Marshal in 1189, he rebuilt the baileys and increased their number, so that there are now three; the Lower, Middle and Upper Baileys. The complex thus forms a line of three baileys running along the ridge, with the main gatehouse at the eastern end of the Lower Bailey, and theGreatTowerrising between the Middle and Upper Baileys. Marshal’s work began in the Lower Bailey with the construction of the twin-towered gatehouse, and continued with the building of a wall between the Lower and Middle Baileys. In this were two round towers; one at the southern junction with the lower bailey curtain, overlooking the Dell, and the other towards the northern end. He rebuilt the southern curtain walls of the Middle and Upper Baileys overlooking the Dell, both connected to the walls of the Great Tower, and at the SW angle of the Upper Bailey he built Marshal’s Tower, a large rectangular structure with luxurious residential quarters over a kitchen, that may have served as a private retreat. After William Marshal’s death he was succeeded by his five sons in turn. In this period, between the death of William Marshal in 1219 and the death of the last two sons, Walter and Anselm, in 1245, an Upper Barbican with a simple gatehouse and a round SW tower was added to the western end of the Upper Bailey. TheGreatTowerwas remodelled in two phases, adding new windows to the upper storey, and adding an extra storey its west end to provide more accommodation. In 1245, the Marshal estates were divided between his five surviving daughters, with Chepstow going to Maud, the eldest of them. She was the wife of Hugh Bigod, 3rd Earl of Norfolk, and on her death in 1248, their son Roger Bigod inherited Chepstow. The next building work we know of was carried out by Roger Bigod’s nephew and heir, another Roger and the 5th Earl of Norfolk. Incomplete building accounts exist from the years between 1271 and 1304, documenting his construction of a grand suite of apartments against the north curtain wall of the Lower Bailey, overlooking the river, by the Master Mason Ralph Gogun ofLondon. Roger Bigod and Ralph Gogun also built the great Marten’s Tower at the SE angle of the Lower Bailey, and again remodelled the 11thc Great Tower, extending the Marshal brothers’ extra storey at the west end to cover the entire tower, adding corner turrets at the eastern angles, and inserting a floor over the hall.

The castle was a Royalist stronghold, held by Henry, 1st Marquess of Worcester, during the Civil War, and was successfully besieged twice; in 1645 and 1648. In the latter siege it was occupied by Royalist troops retreating from Cromwell’s advance to Pembroke; its battlements were razed and the interior bombarded with artillery shells. The Marquess of Worcester’s estates were forfeited to Cromwell, who carried out sufficient repairs to allow its use as a barracks. After the Restoration the Marquess was reinstated, but the king retained Chepstow as a barracks, appointing Henry, Lord Herbert, the heir, as governor. Henry continued the repair work begun by Cromwell, but after he succeeded to his father’s titles in 1667 he preferred to live at Badminton House, a Palladian mansion in Gloucestershire. In the 18thc much of the Lower Bailey was given over to industrial use; including a nail-making works, a glass-blowing retort for making bottles and a maltings. The industrial works were removed in the 19thc, and the interior cleared out and landscaped. Conservation of the fabric was begun towards the end of the century by the Beaufort estate, which then held the castle, and was continued by the Lysaght family who acquired it in 1905. In 1953 Mr D. R. Lysaght put the castle in the guardianship of the state.

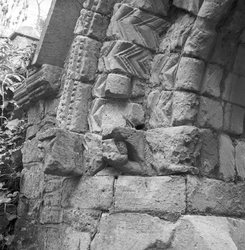

Romanesque interest centres on the 11thc Great Tower, with its chip-carved east doorway and blind-arcaded interior. Some of William Marshal’s work also falls into our period, but there is little or no carved decoration surviving. It will be as well to describe the 11thc features of the Great Tower in some detail here before turning to its individual features. The tower is rectangular; 36m long and 14m wide (120ft by 45ft). It stands on ground that rises from east to west so that the undercroft floor slopes upwards in that direction, and the east end is carried on a high stone plinth. This may be entered by a doorway at the east end of the north wall, and contains no windows. Above this is the Lower Hall, to which the east doorway, originally reached via a timber staircase, gave access. The Lower Hall has three plain, round-headed windows in its north wall, and in the thickness of the east wall is a narrow staircase running from alongside the main doorway up to the NE corner of the Upper Hall, which was the main room. This hall has undergone a good deal of remodelling, but its 11thc form can be reconstructed to some extent. In the north wall was a row of seven round-headed windows. Only the easternmost of them survives, but the jambs of some of the others, formed of a distinctive yellow stone, can be made out. Between the second and third window from the west is a narrow, plain round-headed doorway that must have originally been accessed from an external staircase. The west interior wall has two plain oculi in the gable, and below them it is decorated with a blind arcade of four bays. The blind arcading continues along the S wall, but this wall has been remodelled. At its west end are four complete bays of blind arcading and the springing of a fifth, now blocked; while towards the east end is one bay with the springing of two more flanking it. To the west of this group is a round-headed window, and west of that two lengths of stringcourse divided by the traces of another, wider arch in the masonry. It has been suggested (Turner 2004) that the situation has been further complicated by the installation of a fireplace where the wider arch now is. Turner’s reconstruction of this wall shows a wide niche placed approximately centrally with four niches to the east of it and five to the west. The window is discounted as a later modification. He also suggests that the blind arcading may have continued on the east wall. The east wall now contains a pair of 13thc lancets, but disturbances in the masonry suggest that they may have replaced 11thc windows. The exterior of the Great Tower is articulated with pilaster buttresses, and a decorative band of reused Roman tiles runs right around it, just below the level of the apex of the east doorway, and rising to frame it. Construction is generally of large blocks of grey coursed rubble, but the pilasters are of yellow sandstone blocks, more accurately squared, that may be reused Roman material. The east doorway and the blind arcading are described in more detail below.

Castle

Colchester is the largest town in Essex by population, although it is neither the county town nor does it have a cathedral, both distinctions belonging to Chelmsford. It is in the NE of the county, 50 miles NE of London to which it is linked by the A12 and the Great Eastern main line into Liverpool Street station.

The castle was built using the podium of the Roman Temple of Claudius as foundation for the keep, and is built of rubble including septaria and stone and tile quarried from Roman buildings around the town. The keep is the largest ever built in England with a footprint of 152 by 110 feet (46m × 34m). In form it is a hall keep (rather than a tower keep, like Castle Hedingham). Its long axis runs from N to S, with the main entrance at the W end of the S wall. At the S end of the E wall is an apsidal projection that housed the chapel. The castle is now 2 storeys high, but might have been higher when first built. The only Romanesque sculpture surviving is on the S doorway.

Castle

Conisbrough Castle stands above the River Don on a natural limestone and clay hill. The remains consist of an outer bailey bounded by earthworks, an inner bailey of c.1200, and a stone keep, which is the earliest and most significant building remaining on the site. Extensive damage to the gates, bridge, and walls of the castle was recorded in 1537-8; in addition one floor of the keep had by that time probably fallen in. (Renn 1973,155-7; Toy 1966, 105-7.) Conisbrough and its chapel was used by Sir Walter Scott as the setting for his novel Ivanhoe. The keep, built of fine limestone ashlar c.1180-1202 (see below, History, chapel, for the dates) is cylindrical with six trapezoidal projecting buttresses, the whole keep on a splayed base. The sides of the buttresses have alternate courses of plinth and chamfered stone. The diameter of the base is 19 m; the thickness of the walls above the splayed base 4.6 m and the highest point of the surviving keep is 28 m above ground. There is a single main room at all four levels: a vaulted storage chamber and well in the basement, a work and storage area at the entrance (first) level, the hall on the second floor, the chamber on the third floor with a chapel and sacristy lying off it, and the roof level with a wall walk. Each of the second and third floors has a window, fireplace, stone lavabo basin and latrine. The internal floors and roof were rebuilt in the mid 1990s, until then the sculpture on the fireplaces was open to the rain. The Lord’s apartment has a private chapel. This opens off the main chamber, and is contrived in the thickness of the wall and the SE buttress. The chapel is an approximate elongated hexagon, and is vaulted in two bays. A small L-shaped vestry opens off it on the N wall in the first bay. The stonework in the chapel appears to be damp in the vaulting. There is sculpture on the fireplaces on the second and third floors, and in the chapel on the third floor. The N and S walls of the chapel have circular windows in the buttress, these are quatrefoil on the outside.

Castle

The castle at Devizes has a reset arch containing 12th century stones and another smaller one with reused stones. However, despite having been the site of a major Norman castle, these stones originated at St John’s church. They were part of the west façade which was replaced in 1863. In addition to these stones there are the famous wooden heads which may have originated from the castle but equally could have come from another major building in the town or the area. They have been suggested to be 12th century in date, but are probably more plausibly 13th century in date. In addition to the stones found at the castle, a number of buildings in the town contain reset fragments from the castle, such as at 1 St John's Court.

Castle

Hastings Castle is positioned high above the seafront and has been partially destroyed by cliff erosion along its S side. The chief remains are the N and E curtain walls with an E gatehouse and bastion. The collegiate church of St Mary within the castle is in ruins. There is no Romanesque sculpture in situ.